FEATURE: Was ard found in Bucks river an offering to gods for another fruitful plough?

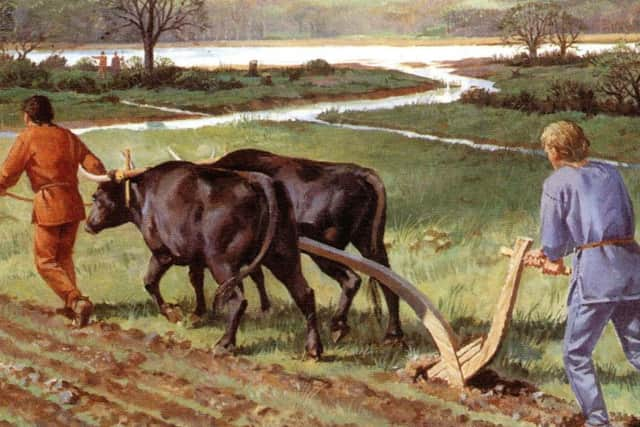

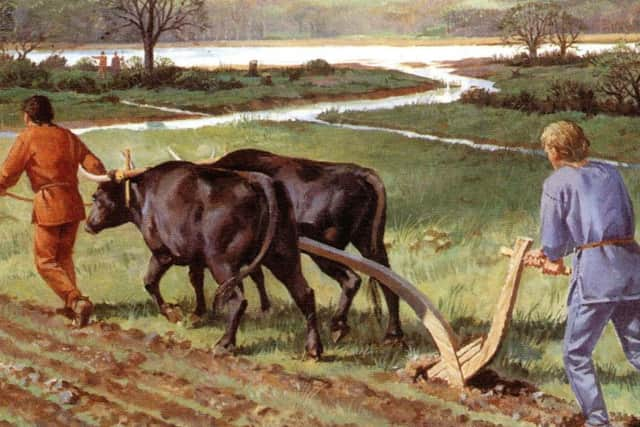

Our third object is a remarkable survival that symbolises a fundamental change in the relationship between our ancestors and the landscape around them: a wooden ard or plough share.

The ard is the simplest form of plough which involved two oxen dragging a wooden share through the ground to lift and break up the ground before sowing seed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOur example was found in the 1990s during the construction of Eton College’s Rowing Lake at Dorney.

Ahead of the development, Oxford Archaeology dug trenches across an abandoned channel of the river Thames.

They discovered a series of timber bridges dating to the Bronze Age and Iron Age alongside which were deposited animal and human bones, pottery, charred cereal grains and the ard share.

On dry land all the wooden objects would have decayed away long ago but in the muddy airless channel they survived in pristine condition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ard-head and stilt is formed from a half split log of Field Maple.

The head is arrow-shaped and 33cm long.

The lower surface of the head has been shaped to be slightly convex and rises towards the tip.

This surface still carries evidence of faint toolmarks.

The tip may have been broken in antiquity as it is very blunt.

The ard is something that most prehistoric families would have owned and relied upon for their daily bread.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey were sometimes tipped with stone or metal but only a handful of wooden ard shares have been discovered in Britain, and this may be the oldest so far as radio-carbon dating suggests it was made between 940 and 560 BC.

By this time, towards the end of the Bronze Age, the rich soils of the Thames Valley had seen increasingly widespread and systematic cultivation for over 1,000 years.

The landscape had been transformed by competing local communities dividing it up into ditched and hedged fields and building forts at commanding points along the river, notably at Taplow and near Marlow.

With a growing population much more effort was put into managing the land productively by managing herds of cattle and flocks of sheep, and ploughing larger areas to grow wheat and barley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArds would have been used across the whole county: contemporary settlements together with tools and weapons made of bronze have been found around Aylesbury and on Ivinghoe Beacon.

In Milton Keynes a remarkable hoard of gold neck rings were found a few years ago buried in a clay pot.

This rising population and new emphasis on personal status and military prowess is characteristic of the time and could ultimately only be sustained by more productive agriculture.

Although the ard was a utilitarian object, its end was more connected with the realm of ritual and spirituality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor more than two hundred years people have been making unusual prehistoric discoveries along the Thames, often brought to light by dredging or building work.

Most dramatic are Celtic shields and helmets, more common are swords and spearheads and human skulls.

It has long been supposed that these are votive deposits, perhaps offerings to the god of the river.

The excavations at Dorney Rowing Lake revealed for the first time how some artefacts were deposited into the river from bridges, and that ordinary objects like pottery and grain could get similar treatment to fine metalwork and human remains.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe will never know who placed our ard head in the river nor precisely why they did so but it was most likely an offering.

Perhaps it was old, had been replaced and was offered in thanks with other gifts in the hope that the river god would bless the next plough to be a fruitful as the last?

For us today the Dorney ard is a memory of the ordinary farmers of prehistoric Buckinghamshire.

It reminds us of the innumerable common folk who tilled the land, herded animals, and lived in thatched wattle huts.

Feature courtesy of the Bucks Archaeological Society