FEATURE: 'Pooley's folley' County Hall still dividing opinion 50 years on

Known as ‘Pooley’s Folley’ after celebrated architect Fred Pooley, it has been immortalised with Grade II listed status.

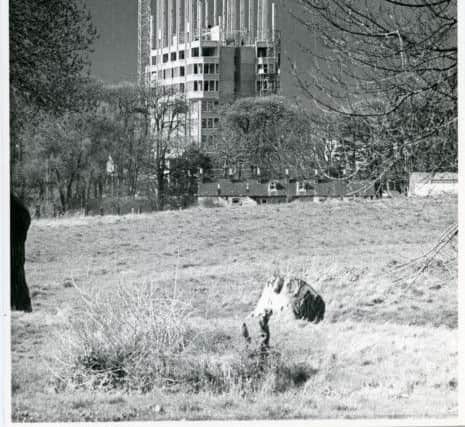

A beacon of the town, the building’s Brutalist style wouldn’t look out of place in a J.G Ballard novel, or a dystopian fiction. It is visible from miles around – it gives us a strange reminder of the zenith of the brutalist architecture and the then architectural visions of future buildings, with its morass of glass and concrete.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The building stands 200ft high and consists of 15 floors sitting above a complex containing the County Reference Library, Aylesbury Register Office and the County Record Office. The height of the building is no coincidence, rather intentional as architects looked to build upwards rather than outwards to save space on valuable green-belt land.

Costing nearly £1million in 1966, it certainly comes as quite a shock to the system of first viewing.

Its stature leaves you in no doubt that despite what you think of its aesthetics, this is an important and iconic piece of architecture.

Fred Pooley wrote about the building: “I accept that as a piece of architecture, the new county offices will be judged by history either as a miserable failure or as a building which made a contribution to the development of world architecture.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“It is one of the first pieces of architecture of its kind that has been manufactured away from the site and assembled on it.”

Despite its unusual appearance – Pooley suggested he wanted it “to blend and be complimentary to the town centre as a whole”. It is difficult to see how this is true, as it contrasts sharply with Aylesbury’s predominantly low rise 18th-century architecture.

Although he suggests that he anticipated Aylesbury to grow and grow: “The scale of this building in the centre of the town is right when one considers the likely ultimate size of the town.”

Every aspect of this building was fully intended by its architect: “The new offices in Aylesbury are essentially important to the town and its population and they should not only be in a convenient central position but designed in such a way to encourage people to take an active interest in their local government.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A futuristic building, designed for the future, but one that seems to be strangley dated in 2016. With its Brutalist roots in the 1940s and earlier, Aylesbury’s County Hall was, like its classical predecessor, already dated by the time of its 1966 completion. By then architecture was moving on to the cleaner and straighter lines and sheets of plate glass advocated by such architects as Mies van der Rohe.

Councillor and architect, Warren Whyte, said: “It’s a building of confliction emotions for me. I’m always impressed by the vision of the council in the 1960s to consolodate all services into one iconic building that captures the spirit of the age. It was an ambitious project, but I’m afraid it became rather tainted by the Friars Square development, which I think is unfair. In terms of style, it was built to a budget. It’s simple and very utilitarian inside, although it’s not without issues. Almost as soon as it opened people complained about the lifts being unfit for purpose, and this is still an issue today.”

Regarding the legacy of brutalist architecture, he added: “ It’s not a style that is easy to love, but as we have seen with the Southbank Centre and National Theatre in London, it does lend itself to a lot of iconic buildings that have over the years gained a grudging respect. It really does define an era. “

Cllr White also suggested that Coventry, where Pooley learnt his trade, may have inspired such a forward thinking architectural passion, after the town was all but razed to the ground following the Second World War. He also suggested that it was the reaction to this building, Pooley’s last modernist effort, that led to him developing more traditional tastes in his future buildings.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Pooley qualified as an architect at the Royal Institute of British Architecture in 1940, before serving with the Royal Engineers during the Second World War.

He worked for the Buckinghamshire County Council from 1953 to 1974, and was awarded the CBE in 1968 for his services to British architecture. His resume includes the Great Missenden Library in 1970; Aylesbury Police HQ in 1959; Buckingham Library in 1962; Wendover Library in 1967 and Aylesbury College in 1963.